The Swedish sin: reflexive possessive pronouns

Have you come across the words

sin,

sitt and

sina in Swedish and feel confused about them? Let’s talk about the Swedish sin!

I’m joking a bit when I call it The Swedish Sin. This phrase is an internationally known phenomenon that has influenced foreigners’ views on Swedish women for years.

The source of it is a speech given by US president Dwight D Eisenhower in 1960, in which he claimed that “sin, nudity, drunkenness and suicide” in Sweden were due to welfare policy excess.

People soon forgot the link to welfare policy, but the myth about the Swedish sin remained…

Reflexive possessive ‘sin’

However, here we’re discussing a different kind of sin. 🙂 The reflexive possessive pronoun

sin.

It is a grammatical issue in Swedish that many, especially English speakers, find difficult. So let’s look at the reflexive possessive pronouns

sin, sitt and sina.

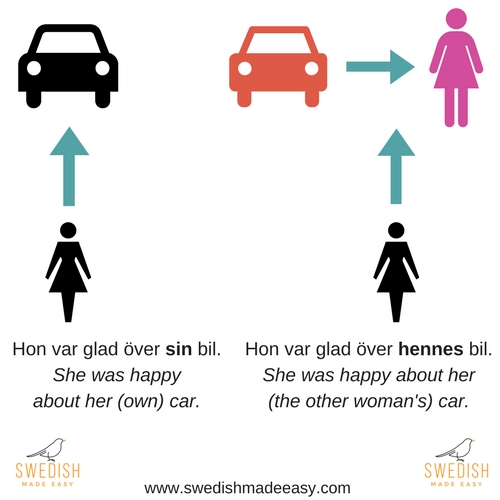

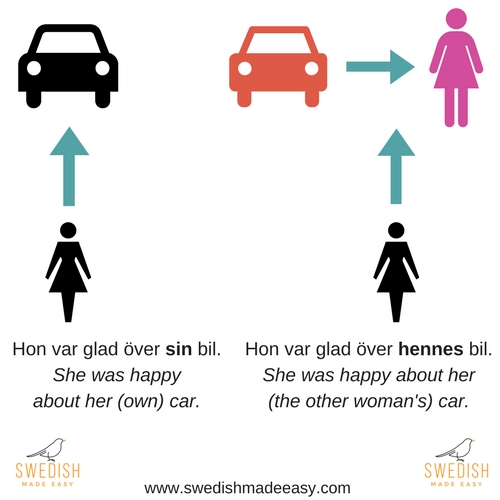

I personally think that the Swedish language is pretty neat in this way, that we can easily distinguish between:

- Hon pratade med grannen om hennes bil. She spoke to the neighbour about the neighbour’s car.

- Hon pratade med grannen om sin bil. She spoke to the neighbour about her (own) car.

Isn’t it pretty cool to be able to clarify that with the uses of

hennes and

sin? This distinction does not exist in English, which can give rise to confusion (and require clarification about who you are actually referring to).

When do we use the Swedish sin, sitt, sina?

We use this reflexive possessive pronoun when we say that the noun belongs to the subject in the sentence.

Hon talade om sin bil. She talked about her (own) car.

The word

sin links back to the subject (

hon), and means that the car belongs to the subject.

We use

sin in this example, because

sin is the

en-word version – and the word

bil is an

en-word. If it was an

ett-word instead, let’s say

hus, then the sentence would look like this:

- Hon pratade om sitt hus. She spoke about her (own) house.

We would use

sitt, because this is the

ett-word version of this reflexive possessive pronoun.

Sin and

sitt are used when the noun is singular (just one thing).

If the noun is in plural, you would use the plural-version (regardless of whether the noun is

en or

ett in singular) –

sina – like this:

- Hon pratade om sina bilar. She spoke about his own cars.

But if she was talking to her neighbour about the neighbour’s house, or cars, the sentences would look like this:

- Hon pratade med grannen om hennes hus. She spoke about her house(s).

- Hon pratade med grannen om hennes bilar. She spoke about her cars.

So the important thing is that the noun belongs to the subject of the sentence. If so, you use

sin,

sitt, or

sina.

Only use in third person!

Sin,

sitt,

sina are only used in this way for the third person – both singular and plural. So, in other words, this only kicks in when you talk about someone else (not

jag or

du). It could be

han or

hon, or

de. It could also be when you use people’s names when you talk about them in third person.

However, it is important to remember that we only use sin, sitt, sina when it is in the object position. We do not use it when the noun is a part of the subject.

Hon pratade länge med sin granne. She talked for a long time with her neighbour.

Here,

hon is the subject and

sin granne is the object.

It can never be a subject

Hon pratade länge med sin granne. She talked for a long time with her neighbour.

Here,

hon is the subject and

sin granne is the object.

Hon och hennes granne pratade länge. She and her neighbour talked for a long time.

But here,

hon och hennes granne are together the subject. In this case, we use

hennes instead

as

sin/sitt/sina can never be a part of the subject in a sentence.

The future of Swedish sin

Interestingly, according to research, this distinction is become more blurred – especially among young people who do not have Swedish as their mother tongue.

They are less likely to use

sin,

sitt,

sina and would instead use

hans,

hennes or

deras. They are also particularly likely to use

hans,

hennes or

deras after a preposition, such as

på or

av.

So for example:

Vem är han arg på? Who is he angry at (/with)? På hans mamma. (At) his mother.

Whereas those who have Swedish as a mother tongue are more likely to say

På sin mamma, in this case.

But does this mean that this grammatical rule is slowly changing?

Researchers are divided, but it seems that this kind of use of the reflexive possessive pronoun does not influence “mother tongue speakers”, so it seems unlikely that the rule will change within a near future, even though examples of alternative uses may become more common in the future.

Share this with someone who needs it!